Washington Post: When last summer’s devastating flood put the town of Waverly, Tenn., underwater, Richard Rye was standing on the roof of the junior high school. The junior high school where, if it had not been a Saturday morning, entire classrooms of kids would have been submerged in five feet of water as a rising swell pushed through the building, ripping heavy doors off their hinges and turning hallways into rivers, desks bobbing in the current like paper cups.

Rye, the director of schools for Humphreys County, stood on that roof for hours and watched first neighboring Waverly Elementary and then Waverly Junior High School, buildings that housed 1,100 total students on any given weekday, fill with water. All he could think was: What am I going to do?

The forecast had showed only a few inches of rain. And Waverly, a rural town with a smaller-than-average Walmart, a few fast-food chains, an AutoZone and not much else, wasn’t seen as a cosmic center of extreme weather. On the night before the flood, many people, including Rye, had sat under the Friday night lights cheering on the high school football team, the Tigers. When the Tigers won, the rain had not yet started to fall.

Then, early on the morning of Aug. 21, Rye woke to a text message from the elementary school principal alerting him that Trace Creek, which winds its way through Waverly, had started rising.

Picture where you are right now and imagine taking 30 or so long steps. That’s the distance from one corner of the school to the water’s edge. That had always worried Rye, especially since the elementary and junior high schools sat in a low-lying area. When he took over as director in July 2020, they had already flooded twice, in 2010 and 2019. Rye had started to build a raised-dirt berm around the buildings in hopes of keeping flooding at bay — the best he could do with limited resources.

By 7:45 a.m. that Saturday, Rye was in his gray Ford Explorer headed to the schools. Within an hour, Rye and a bus mechanic had loaded a truck bed full of sandbags and were beginning to place them around the perimeter of the elementary and junior high buildings. Water lapped around their ankles. A few minutes later, the water was at their knees, then at their waists. The strength of the water threatened Rye’s balance and felt, he remembers, “like a tsunami.” That’s when Rye, along with a few others who were at the campus, opened a supply closet, got a ladder and climbed to the roof.

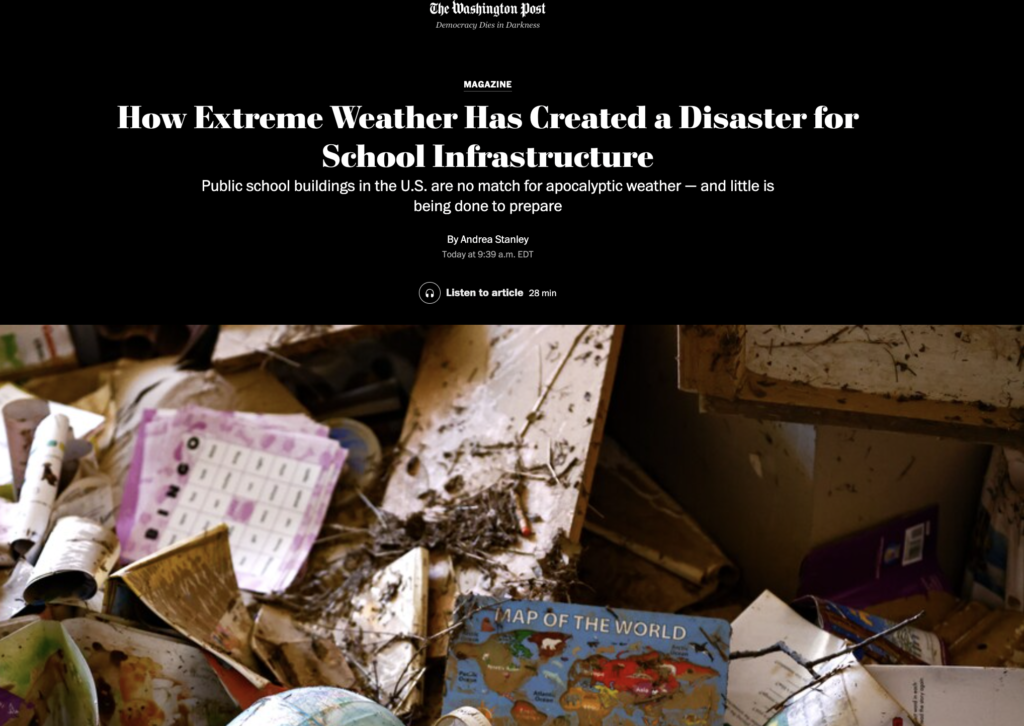

The flood proved catastrophic, dumping at least 17 inches on the area, damaging more than 600 homes and killing 20 people, including three students: a second-grader, a high school freshman and a high school sophomore. But the gravity of what Rye faced in its aftermath made it worse still. Put the children back in the flood basin? If not that, then where?

It’s a question more school officials will need to answer in the coming years. In January the U.S. Government Accountability Office released a report on the impacts of weather and climate disasters on schools, finding that “Over one-half of public school districts [are] in counties that experienced presidentially-declared major disasters from 2017 to 2019. These school districts included over two-thirds of all students across the country.” It’s a big number that is likely not big enough; the country has seen only larger and more widespread climate catastrophes in the years following the report. The year 2020 holds the record for the most “billion-dollar” weather and climate disasters since the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information began keeping track. The second highest year was 2021.

In the West, wildfires are turning schools to ash-paste; in the South, floods are the ever-present threat. It’s a threat that is growing larger, yet is often overlooked, especially in rural communities. There, it’s not just hurricanes washing away neighborhoods, but inland flooding, a phenomenon that happens when smaller bodies of water become overwhelmed by increasing precipitation. A 2017 report by the Pew Charitable Trusts found that nearly 6,500 public schools are in counties at a high risk of flooding, and that number is rapidly multiplying; a study published in Nature in January found that the nation’s flood risk will jump 26 percent in the next three decades. Read more>>